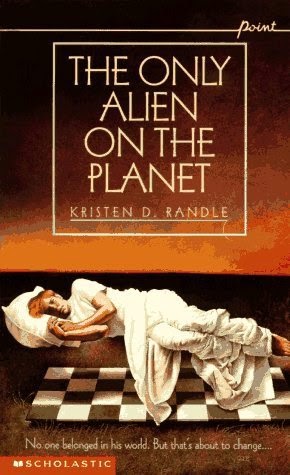

Today we're talking about The Long Earth, a recent science-fiction collaboration between Terry Pratchett and Stephen Baxter. Apparently it also has a sequel, which google just told me, and I will be sure to check that out. Since I just found out about that, though, bear in mind that this review kind of hinges on me not having read the sequel.

So, The Long Earth is a conceptual sci-fi novel based on a pretty cool premise: What if our Earth is just one in an almost-infinite string of Earths, all layered on top of each other like a deck of cards? And what if we could get from one Earth to another with just a single step? How would that change us as people? How would that change the world? And what would we find when we kept on stepping?

Obviously, these are compelling questions, and these are the questions that the novel seeks to answer. Going in every-so-vaguely chronological order, the book shows us Earth, our Earth or maybe not, on and around "Step Day" - the day that everyone on the planet found out about the Long Earth. One day there were plans, available for free online, of how to build your own "Stepper". No one knew what they did, but as soon as the Steppers were turned on, thousands disappeared, only to reappear in empty worlds. Two empty worlds, to be precise: Earth West 1 and Earth East 1. Those are the two directions you can step. East or West. And each time, you can only step to one new world.

Well, sort of. It's complicated. Let's leave it at that.

Our main-ish character is Joshua Valiente, a strange boy raised in a group home by a bunch of really unusual nuns. Joshua stepped on Step Day, like every other kid his age, but unlike all those kids, Joshua didn't get sick or scared, and he didn't freak out. He just calmly noted that he was somewhere new, and then helped everyone else get back. Then, when being questioned, Joshua freaked out and stepped without using his Stepper - which shouldn't be possible. Joshua is weird. Joshua is an enigma to the authorities. And Joshua might just be the key to figuring out what the Long Earth is for.

The book then follows about ten years after Step Day, as the world comes to grips with the idea of limitless Earths. At first everyone ventures a little bit away from home, going to Earth West 1 and 2, or whatever, but as time goes on, they step further and further away. Joshua goes in front, like a modern Daniel Boone, always heading out when he sees signs of people coming closer, but then doubling back to say hi to the nuns again, or get his mail. It's on one of these returns to the Datum (the original, inhabited Earth), that he is picked up by the Black Corporation, in order to have an audience with Lobsang. Lobsang is a computer. Lobsang is also, possibly, the reincarnation of a Tibetan motorcycle repairman.

Lobsang is interested in the Long Earth. And Joshua. And lots of things.

But he's most interested in the Long Earth and Joshua. He's willing to blackmail Joshua into taking him out into the Long Earth, into the "High Meggers" - or Earth's a couple of million Earths away - in order to see if there is an end to the Long Earth, to see what's really out there, to try to understand what has happened. Joshua doesn't really have a choice, but it's an intriguing prospect. And so they're off.

That's not the only storyline, of course. There's also the story of Detective Monica Jansson, who ends up heading the Madison, WI response to Step Day, and goes forward as the only person who really understands what stepping means for public policy. And the narrative dabbles with other results, like families that step out into the wild yonder like old time prospectors or settlers. But most interestingly to me, the story deals, if only vaguely, with those people who cannot step. The "phobics", as they're called. And this is where my critique of the book starts.

I mean, it's only a critique insofar as I wish it were different. I don't actually have the answers to these questions, but I rather wish that Baxter and Pratchett did. Because the problem with the book, that I can see, is that it's far too concerned with the exploration of the ideas of what the Long Earth would mean, and not really enough concerned with making a coherent story.

Like, I agree, this is a fascinating concept, and I love the little ways that it explores what would happen ten years down the line as scarcity is literally removed, as a fifth of Earth's population abandons the planet, and as another fifth of the population is forced to stay at home, forever. I love the little weirdnesses in the book, with alternate evolutions on alternate Earths, with the "trolls" and "elves", which are alternate hominids that aren't quite human but are certainly interesting. And the whole idea of the Silence and Joshua's birth and all that jazz. It's all really interesting, sure, but it's not really enough.

Nothing really happens in this book. And that bothers me.

Joshua and Lobsang make this epic journey to the far reaches of the Long Earth, finding all kinds of insane and bizarre worlds along the way, eventually picking up a hitchhiker, Sally, and going all the way out until they find something a bit scary: a sentient ocean called First Person Singular, that has the potential to destroy all life in all the Long Earths. And you know what happens when, after four hundred pages, they meet this creature? Lobsang joins with it psychically, and Joshua and Sally go home. That's it.

But wait! It's not the end! There's still the situation back on Datum Earth, where the phobics are becoming more and more radicalized, incensed that they are stuck on this world while others can gallivant through the universes. The phobics turn political, and Rod, a kid whose whole family left him behind to become pioneers out in the Long Earth, brings a nuclear bomb to the center of Madison, WI.

Only in a world with stepping, it's easy not to get caught up in a nuclear blast. Everyone just steps away, and helps those who cannot step, and no one is hurt, not even Rod, and it's all happy endings and huh? I mean, I appreciate philosophically the idea of how hard it is to have a war when everyone can just step around it, but still. Narrative wise, that sucks.

And honestly, narrative wise, the whole book sucks. It's a mass of cool ideas and neat concepts, but poor storytelling, and ultimately limited emotional connection. You don't really care about any of them, because they're less characters than they are examples in the thought experiment that is this book.

Like I said, though, it's not that this is a bad book, per se. And I will read the sequel. I just expected a lot more from this. I expected the kind of emotional connection I usually get in Terry Pratchett's works. But it seems that in reaching for a higher concept and trying to explore that concept to its fullest potential, the book has lost out on engaging deeply enough in any one story to create a meaningful narrative. And that's just too bad.

So, The Long Earth is a conceptual sci-fi novel based on a pretty cool premise: What if our Earth is just one in an almost-infinite string of Earths, all layered on top of each other like a deck of cards? And what if we could get from one Earth to another with just a single step? How would that change us as people? How would that change the world? And what would we find when we kept on stepping?

Obviously, these are compelling questions, and these are the questions that the novel seeks to answer. Going in every-so-vaguely chronological order, the book shows us Earth, our Earth or maybe not, on and around "Step Day" - the day that everyone on the planet found out about the Long Earth. One day there were plans, available for free online, of how to build your own "Stepper". No one knew what they did, but as soon as the Steppers were turned on, thousands disappeared, only to reappear in empty worlds. Two empty worlds, to be precise: Earth West 1 and Earth East 1. Those are the two directions you can step. East or West. And each time, you can only step to one new world.

Well, sort of. It's complicated. Let's leave it at that.

Our main-ish character is Joshua Valiente, a strange boy raised in a group home by a bunch of really unusual nuns. Joshua stepped on Step Day, like every other kid his age, but unlike all those kids, Joshua didn't get sick or scared, and he didn't freak out. He just calmly noted that he was somewhere new, and then helped everyone else get back. Then, when being questioned, Joshua freaked out and stepped without using his Stepper - which shouldn't be possible. Joshua is weird. Joshua is an enigma to the authorities. And Joshua might just be the key to figuring out what the Long Earth is for.

The book then follows about ten years after Step Day, as the world comes to grips with the idea of limitless Earths. At first everyone ventures a little bit away from home, going to Earth West 1 and 2, or whatever, but as time goes on, they step further and further away. Joshua goes in front, like a modern Daniel Boone, always heading out when he sees signs of people coming closer, but then doubling back to say hi to the nuns again, or get his mail. It's on one of these returns to the Datum (the original, inhabited Earth), that he is picked up by the Black Corporation, in order to have an audience with Lobsang. Lobsang is a computer. Lobsang is also, possibly, the reincarnation of a Tibetan motorcycle repairman.

Lobsang is interested in the Long Earth. And Joshua. And lots of things.

But he's most interested in the Long Earth and Joshua. He's willing to blackmail Joshua into taking him out into the Long Earth, into the "High Meggers" - or Earth's a couple of million Earths away - in order to see if there is an end to the Long Earth, to see what's really out there, to try to understand what has happened. Joshua doesn't really have a choice, but it's an intriguing prospect. And so they're off.

That's not the only storyline, of course. There's also the story of Detective Monica Jansson, who ends up heading the Madison, WI response to Step Day, and goes forward as the only person who really understands what stepping means for public policy. And the narrative dabbles with other results, like families that step out into the wild yonder like old time prospectors or settlers. But most interestingly to me, the story deals, if only vaguely, with those people who cannot step. The "phobics", as they're called. And this is where my critique of the book starts.

I mean, it's only a critique insofar as I wish it were different. I don't actually have the answers to these questions, but I rather wish that Baxter and Pratchett did. Because the problem with the book, that I can see, is that it's far too concerned with the exploration of the ideas of what the Long Earth would mean, and not really enough concerned with making a coherent story.

Like, I agree, this is a fascinating concept, and I love the little ways that it explores what would happen ten years down the line as scarcity is literally removed, as a fifth of Earth's population abandons the planet, and as another fifth of the population is forced to stay at home, forever. I love the little weirdnesses in the book, with alternate evolutions on alternate Earths, with the "trolls" and "elves", which are alternate hominids that aren't quite human but are certainly interesting. And the whole idea of the Silence and Joshua's birth and all that jazz. It's all really interesting, sure, but it's not really enough.

Nothing really happens in this book. And that bothers me.

Joshua and Lobsang make this epic journey to the far reaches of the Long Earth, finding all kinds of insane and bizarre worlds along the way, eventually picking up a hitchhiker, Sally, and going all the way out until they find something a bit scary: a sentient ocean called First Person Singular, that has the potential to destroy all life in all the Long Earths. And you know what happens when, after four hundred pages, they meet this creature? Lobsang joins with it psychically, and Joshua and Sally go home. That's it.

But wait! It's not the end! There's still the situation back on Datum Earth, where the phobics are becoming more and more radicalized, incensed that they are stuck on this world while others can gallivant through the universes. The phobics turn political, and Rod, a kid whose whole family left him behind to become pioneers out in the Long Earth, brings a nuclear bomb to the center of Madison, WI.

Only in a world with stepping, it's easy not to get caught up in a nuclear blast. Everyone just steps away, and helps those who cannot step, and no one is hurt, not even Rod, and it's all happy endings and huh? I mean, I appreciate philosophically the idea of how hard it is to have a war when everyone can just step around it, but still. Narrative wise, that sucks.

And honestly, narrative wise, the whole book sucks. It's a mass of cool ideas and neat concepts, but poor storytelling, and ultimately limited emotional connection. You don't really care about any of them, because they're less characters than they are examples in the thought experiment that is this book.

Like I said, though, it's not that this is a bad book, per se. And I will read the sequel. I just expected a lot more from this. I expected the kind of emotional connection I usually get in Terry Pratchett's works. But it seems that in reaching for a higher concept and trying to explore that concept to its fullest potential, the book has lost out on engaging deeply enough in any one story to create a meaningful narrative. And that's just too bad.